J.B. Jackson, in his book Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, wrote “No group sets out to create a landscape of course. What it sets out to do is to create a community, and the landscape as its visible manifestation is simply the by-product of people working and living, sometimes coming together, sometimes staying apart, but always recognizing their interdependence.” This spirit of community and collaboration couldn’t be more evident than in Stamford, Connecticut during the city’s recent opening celebration of Mill River Park. Residents gathered for a weekend of festivities along the banks of Mill River, commemorating the long anticipated 14-acre park and river restoration by the Army Corps of Engineers and park design by OLIN—a nearly decade-long project. But the full story of Mill River’s evolution reaches much farther back into Stamford’s history.

Riffles and pools replace the dam and canal walls at Mill River Park © Sahar Coston-Hardy

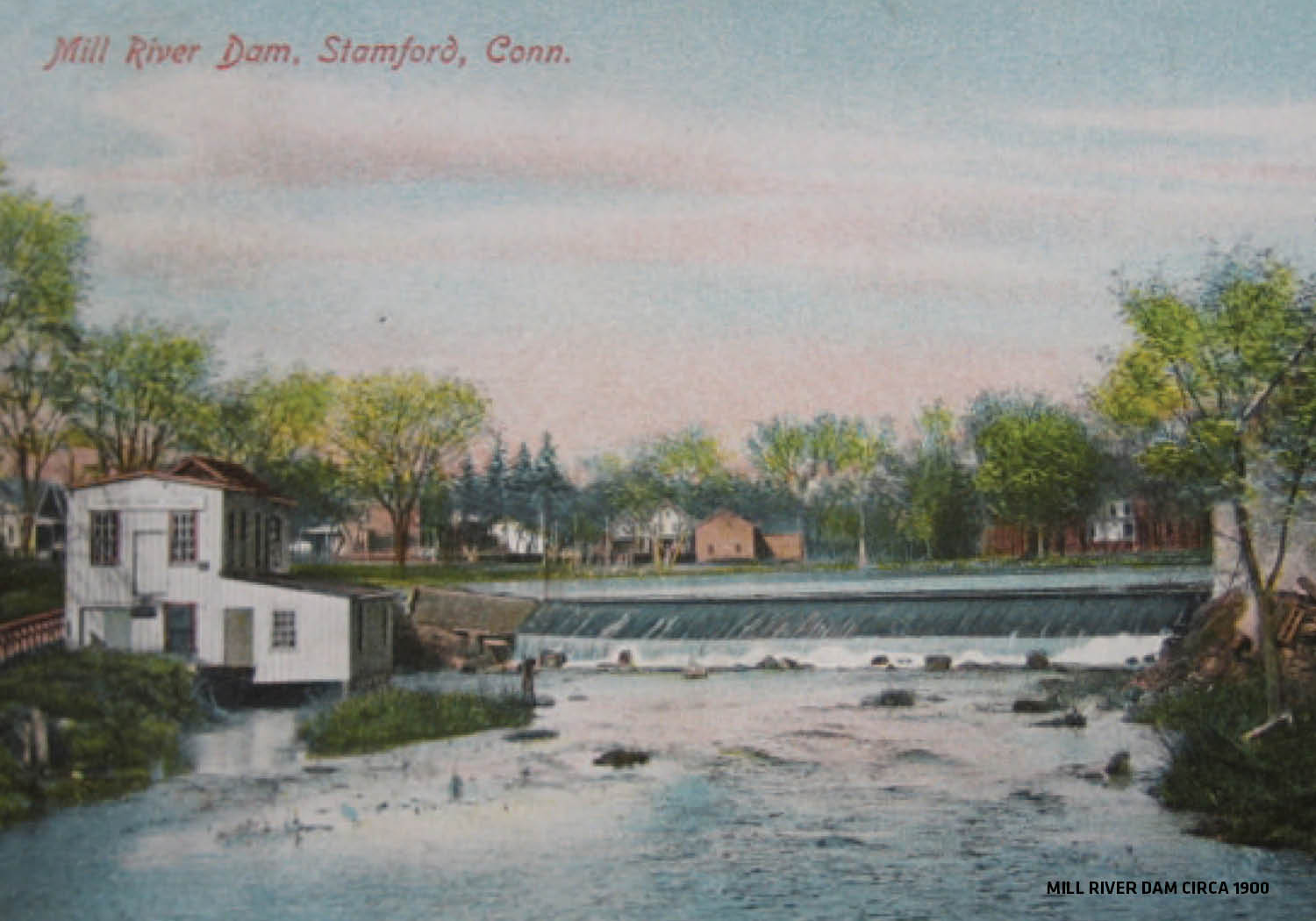

The Rippowam River, a name given to the meandering waterway by the native Algonquin peoples who once inhabited its banks, has been the backbone of the Stamford community for centuries. The river stretches 17 miles inland from portions of Connecticut and New York State through the West Branch of Stamford Harbor and into Long Island Sound. The lower nine miles of the Rippowam courses through the center of what is now Downtown Stamford and was coined Mill River in 1642, when the area’s first Puritan settlers dammed the river to create the town’s original gristmill, and the lowland area upriver of the dam became known as Mill Pond. Ever since, Mill River has been the focus of intense industry and the key to economic prosperity for the area.

Postcard circa 1900

Stamford has evolved dramatically over time, from its early stages as a Puritan outpost, to an industrial mill and manufacturing center, to what is now a home base for major corporations. But as with many urban landscapes, Mill River’s natural systems have suffered the ill effects of industrial and economic progress.

Plan of Mill River circa 1870

By the turn of the 19th century, the dam had been used as a carding mill, rolling mill, a foundry, and a woolen mill. In 1922, in an effort to protect its people and infrastructure from flood risk, the City of Stamford rebuilt the dam and narrowed the pond by constructing 15-foot high canal walls on the eastern and western sides of the impoundment. In 1929, city planner Herbert Swan proposed his Plan of a Metropolitan Suburb, proposing an “Olmstedian” vision for Stamford. The plan focused on creating open space along waterways and preserving the unique character of Stamford’s picturesque natural systems that Swan contended were “unexcelled anywhere in the New York metropolitan area.’” He wrote, “In developing its plan, [Stamford] should accentuate those things which it has received either through inheritance or through nature that differentiate it from other communities…the points of difference in the plan are its points of excellence; it is these which, if properly understood and sympathetically employed…afford the strength and interesting originality to a plan and give the city individuality and character.”

Herbert Swan’s Comprehensive Plan for Stamford

One of Swan’s recommendations was for a Rippowam River Park, “through which flow tiny rivulets, and serves as refuge for birds and lesser animal life.’” Throughout the 20th century, the area around the channelized Mill Pond existed as a network of underutilized lawn areas, paths and benches. One major improvement came in 1957, when Junzo Nojima, a Japanese immigrant, planted a grove of 100 cherry trees in the park. This intervention became a central focal point of the park, beloved by Stamford residents. But unfortunately the park’s other dominant feature—the river—stood out as a barrier and eyesore, with the imposing concrete walls both inhibiting pedestrian access to the water and compromising the river’s natural ecological systems of flow and drainage.

Invasive species and debris stifled Mill River prior to restoration © Mill River Collaborative

To make matters worse, it had become apparent over the years that the channelization of the river, a measure intended to prevent flooding, actually impeded Mill River’s natural defenses against floods. Silt buildup along the dam and impervious canal walls prevented stormwater infiltration, regularly forcing floodwaters over the walls and into surrounding neighborhoods. For decades, excessive amounts of silt, branches, trash, and other debris—everything from soda cans to street signs to cars—collected in Mill Pond, creating a network of unsightly and stagnant pools of brown muck choked with invasive aquatic plants and blooming algae.

Mill River prior to restoration © Mill River Collaborative

Mill River prior to Restoration © Mill River Collaborative

In 1997, as the dam and canal walls were falling further into disrepair, the City of Stamford began to study strategies to improve water and habitat quality in the river, and at the same time reconnect the residents of Stamford to the river and foster urban redevelopment in downtown. In 2000, The Army Corps of Engineers developed a proposal to naturalize the river corridor and remove all obstructions and impoundments from the waterway, allowing Mill River to flow freely for the first time since the 17th century.

Demolition of the Dam © Mill River Collaborative

The demolition and restoration would reverse the effects of the river’s degraded ecological systems and reinstitute wildlife migration patterns—including the passage of anadromous fish (saltwater species that spawn in fresh water)—upriver. Additionally, the restoration would reduce sedimentation into Mill River and beyond. In 2002, a joint effort between then Mayor of Stamford Daniel Malloy, the Stamford Partnership, and the Trust for Public Land led to the founding of the Mill River Collaborative, a partnership of civic, government, and business interests dedicated to realizing a world-class park along Mill River’s banks.

Before and After Restoration © Will Belcher

In 2005, Stamford and the Mill River Collaborative engaged OLIN to create—in collaboration with the Army Corps of Engineers—a plan to restore the meandering river and craft a vision for the park in the same spirit of the plan that Swan proposed more than 75 years before. The plan aimed to achieve three primary goals: create a park that meets the recreational and civic needs of a diverse population, provide a natural habitat for native flora and fauna to flourish, and offer a vision that is economically viable, maintainable, and implementable in phases over time.

Mill River Park at Grand Opening © Will Belcher

OLIN led a team of ecologists and civil engineers, collaborating with experts and engaging the public outreach sessions. Out of the process, a comprehensive and ambitious framework for a park and greenway emerged. The end result: a dynamic park that is viable, active and alluring, a continuous, programmed edge along the banks of Mill River, and a “green zipper” that brings together neighboring communities with downtown Stamford.

Mill River Park and Greenway Masterplan © OLIN

The first phase of the park, which opened at the beginning of May, is the cornerstone for the entire park and greenway. It incorporates a naturalized river way, utilizing riffles, pools, and other stream restoration techniques which allow the river to flow naturally and direct flood waters downstream. This phase also provides areas for active and passive recreation, including the Grand Steps, a series of plinths and boulders which invite users to engage with the river’s edge.

Residents are reunited with their waterfront at the Mill River Park and Greenway Grand Opening © Sahar Coston-Hardy

Another key feature, the Great Lawn, is an expansive green carpet that provides flexible open space for large events and a setting for waterfront entertainment. Thoughtfully placed benches and seating areas along pathways and overlooks encourage moments of contemplation and rest throughout the site. Paving materials were selected for their ability to withstand flooding events. Historic stone walls are maintained, and indigenous stone boulders were unearthed from a nearby construction and incorporated into the project as a celebration of local history and regional geology. A native planting palette is employed across the park—a further expression of regionalism—allowing for educational experiences for residents and visitors. Wildflower blooms and The Cherry Blossom Festival, the largest in New England, provide ephemeral experiences for park users in all seasons. Other programmatic functions, including movies, concerts, and fairs, are scheduled throughout the year by the Mill River Collaborative.

“Spielberg in the Park” drew hundreds of visitors to Grand Opening weekend © Will Belcher

OLIN’s work, however, is far from complete. The studio is currently involved in several new phases of the park, including the rehabilitation and beautification of Tresser Bridge and key streetscape improvements along the Tresser corridor. Additionally, OLIN is working on the extension of the Park and Greenway southward to the Stamford Harbor. Future phases include a carousel pavilion and covered porch designed by Gray Organschi Architecture, a dynamic fountain, ice skating rink, and restroom pavilion designed by River Architects, and whimsical playground restrooms by Rogers Marvel Architects.

Mill River Park Grand Opening Weekend © Sahar Coston Hardy

As Mill River Park and Greenway continues to evolve, the commitment and vision by private and public partnerships is firmly in place. Each phase brought to life from the pages of the master plan will weave together the Stamford community, creating a distinctive public realm. The park and greenway will be a place like no other in the region, one that showcases local flora and fauna, restores natural ecological systems, fosters new urban redevelopment, and celebrates community through diverse programming and daily enjoyment. And of course, as with Mill River’s own storied past, this park will surely continue to evolve for generations to come.